José F. Grave de Peralta

Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda

A new way of LIVING Dangerously: Of reading, drawing, and walking in Rome

Figure above: tourist signpost located in Piazza del Popolo, Rome.

" Cervantes entered Rome"

poem by Rafael Alberti (1968),

from Rome: Danger for Walkers.

"Cervantes entered Rome by way of Piazza del Popolo ....

" Oh great, powerful, and venerable city of the soul: oh Rome!"

he said as he fell down on his knees in humble devotion.

Up from its shadowy rooftops, its towers and cupulas, as it rises to the sky , Rome lifts its head.

Oh Rome of giant doors for the Gods! Today I saw Polyphemus himself walk through one of your gates !"

Halfway through my undergraduate studies in philosophy and classical arts and sciences at St. John’s College in Maryland, U.S.A., I decided to spend a year in Salamanca, Spain, site of one of the three oldest universities in Europe. With my parents’ blessing (and money) I was fortunate to study a few courses in theology in that city’s Pontificia University and read with the help of an old dictionary and of my then-young and very wise tenant in that city, Alfonso, in its original Castilian Spanish, the novel Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes.

The time was Francisco Franco’s Spain – the early 1970s.

I recall the tearful, dramatic embrace I gave my parents and my closest childhood cousin Julio, the night prior to departure from my home in Delaware. But my romanticism pulled me through the separation, and before I knew it I was boarding an Iberia jet for Madrid with a student duffle bag full of sweaters, dreams, and several sketching books and materials, along with a new leather-bound Aguilar edition of Cervantes’ “travel novel” that my mother had brought me from Buenos Aires earlier that year.

On exhibit on this page are a number of pencil and pen drawings, watercolor, and pastel illustrations of much more recent vintage – 2017 and 2018 – in fact not inspired in the adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza that took me to Salamanca in 1972, but in Persiles and Sigismunda a later, perhaps obscure work by the same author, published posthumously to his death (the same day and year as Shakespeare, by many accounts!) and focusing on jealousy and desire as well as on faith and disillusionment in the lives and travels of young people.

Travels in the streets and piazzas of Rome often lead to discovery of various kinds. And I stumbled on a tourism signpost pointing me to Cervantes’ Persiles some ten years ago while I taught perspective and freehand drawing to a small group of University of Miami students of architecture in the lovely urban setting of Piazza del Popolo located at the north end of the historical center of the City. There, while my 8 or 10 students were busily applying our lessons in “sight measuring” and grids to draw various corners of the oval-shaped piazza, my eyes were drawn by a signpost clear on the other side of the obelisk where the class was, with the heading CERVANTES writ large across the top, and a few verses about the 22-year-old author’s first entrance ever into the Eternal City back in the 1570s.

After close inspection of the sign, I walked back to review my students’ lines and told them about the many famous figures from history – including my favorite Spanish author – who had entered in their time through the very gate that they were drawing with their grids. Moreover, if we were to believe the information of the (to us) melodramatic tourist sign, people gathering then by the gate of Piazza del Popolo would not have seen a group like ours of architecture students learning how to draw perspective, but rather the future novelist and soldier of the Battle of Lepanto, falling to the ground on his knees and singing his praises of the Eternal City for all to hear --- as quoted in the metal signpost of the Department of Tourism that caught my eye accidentally in 2008. “Hmmm,” I joked with my students when I pointed out the poetic quote to them in the piazza: “who would think of doing such a thing when arriving here nowadays?” In 2008, my Roman drawing class was already fully knowledgeable in CAD-design, so pencils and sight-measuring as we were using in Piazza del Popolo that day, were obsolete things. Imagine my asking them to relate the art of the sonnet to their overall arching project of design --- already dominated by computer keyboard software and such!

And yet, as I found out when I read the novel in earnest, the "Persiles" turns out to be a compelling novel about young people who use their natural instinct and their sense of poetry to get them to their desired destinations. Its plot is about lovers eloping and hoping to live happily ever after… they pass a series of harrowing as well as humorous trials as they travel to Rome incognito, posing as brother and sister. But is also about domination and sadism, in the narrative form of a ring of international “barbarians” who supposedly abducted beautiful young men and women in their search for the semen and uterus that would produce some crazy, Messianic super race! Of course Cervantes worded the sexual side of the plot very elegantly, but the early scenes are hilarious, with his male hero Persiles cross-dressing and batting his eye lashes in order to gain entrance into the dungeon where his betrothed is waiting to be made the mother of the barbarian redeemer. Later chapters take them face to face with sorcerers, abusive soldiers of the Spanish Inquisition, and even with the problem of Islamic terrorists and religious fanaticism and hypocrisy---in those days not too different from ours.

And while the ethnicity of the two lovers is not quite Spanish – Persiles and Sigismunda are white, Scandinavian Protestants-turning-Catholic – Cervantes’ own problems with the Spanish Inquisition and his 4-year imprisonment in an Ottoman jail in Algiers after his capture right after the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 gave him the blueprint for much of the physical and moral geography of Persiles and Sigismunda. (Few Romans know much about his participation in the Papal Battle of Lepanto, in essence a world war fought to keep the Turks from turning Rome into another Istanbul, and sadly they know much less that the Spanish playwright and novelist had been ransomed from the Ottoman dungeons of Algiers in Northern Africa by the Trinitarian monks in the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane here in Rome who, in the 16th century, mediated the exchange of prisoners Islamic and Christian, incarcerated in connection with Lepanto!)

But in closing the present explanation about how these illustrations came to be, I must acknowledge that when I told my great friend and professor of Spanish literature, Ivo Dominguez, that I had begun to read the novel in earnest and to draw scenes from it, he lost no time in sending me the call for papers at the University of Berkeley, California, on precisely this Cervantine novel! Dominguez and I had been amazed to find that not a few place names of contemporary Rome – for example, Piazza del Popolo, Via dei Banchi Vecchi, and finally the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, were the settings for the most poignant scenes in the year 1600 plot. “The final chapters are a sort of map of modern Rome,” I told my highly esteemed Delaware professor, “and I am going to trace it with my pencil and pastels in order to gain access to the secrets of the novel!”

For students of so many disciplines, Rome is indeed a city of discovery. But I am convinced that in focusing on its principles of design and in its rich history, this discovery can be impeded and biased by the way we walk or talk it or especially graphically represent its lessons of beauty, power, humility, and domination (to name but a few themes). Its lessons of scale, perspective, and ornament are lost if we limit ourselves to machine-directed study and computer enhanced editions of what the city’s streets hide inside them in the form of narrative and moral questions. In short, Miguel de Cervantes, a Catholic author in the deepest sense of the word, does not pussyfoot around his creed in this novel, and when I heard his voice to all effects trembling with loving emotion or rage in some of the episodes of this Roman-centered novel, I knew I had been abducted myself, though not by pirates of some world domination scheme. For me this was a new journey to Salamanca---like that of 1972 – on so many levels, some of them even dangerous.

Not by accident, the poem with which “Cervantes Entered Rome” in my Drawing Class in Piazza del Popolo in 2008 had been written by another poet, Rafael Alberti, in 1968, in a text aptly entitled Roma: Peligros para viandantes: "Rome: Dangers for travelers." Alberti, I learned had fled a previous city of exile from his native Spain, Buenos Aires, due to the demagogic persecutions and intolerance of Juan Domingo Perόn, husband of the famous Evita.

Young Travelers beware. These drawings are … not just drawings

A marvelous occurrence in the Port of Barcelona

(watercolor, 4" x 10")

Periandro torn between Chastity and Sensuality

(pastel, 8" x 8")

Aphorism: " Beauty coupled with honesty is true beauty, and when it is not, it is mere appearance"

(pen & ink, 4" x 6")

Near LUCCA. the pilgrims meet Isabella Castruccio, the "woman possessed"

(pastel, 14" x 18")

The pilgrims find shelter in a belfry during a Moorish kidnapping raid

(ink, 11" x 14")

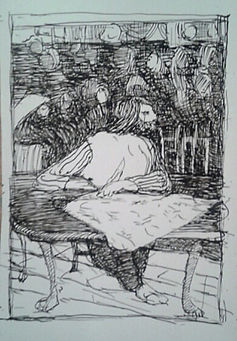

Periandro cross-dresses to liberate Auristela

(ink, 11" x 14")

Diagram of the novel's themes

Aphorism: " Glory won in war and writ in bronze with steel outlasts all other glories"

(pen & ink, 4" x 6")

Periandro in girls' clothing and Auristela are sold to the barbarians by Danish corsair prince Arnaldo

(ink, 11" x 14")

The pilgrim who collected Aphorisms

(ink, 7" x 5")

The pilgrim who collected Aphorisms

(ink, 7" x 5")

The pilgrims are arrested by the Holy Inquisition just as they find a young lover who had just been killed in a duel

(ink, 12" x 8")

The seduction of Periandro by the art gallery owner of Ferrara

(pastel , 24" x 30")

The tragic wedding of Eleonora

(ink, 11" x 14")

The mysterious lady in the Oak

(ink, 11" x 14")

Acquapendente

(ink, 8" x 6")

Acquapendente, on the Francigena Pilgrim Route

(ink, 8" x 6")

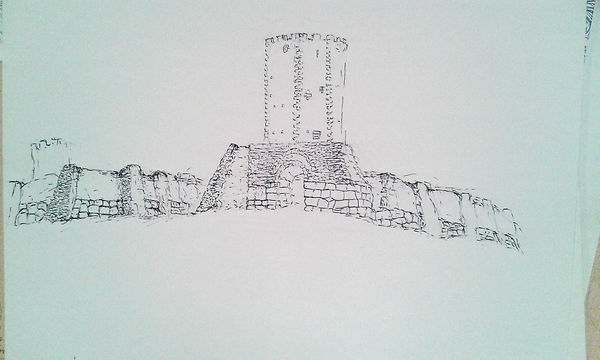

A tower along the Francigena Pilgrim Route

(ink, 11" x 14")

Feliciana de la Voz sings to Our Lady in the shrine of Guadalupe

(ink, 11" x 14")